The Philosophers’ Library

The Philosophers’ Library is a history of philosophy as told through its most important books—sort of. Because in the earliest days of philosophizing, the book format hadn’t been invented yet. And even after it had, many important philosophical insights never quite materialized into book form. Or sought other shapes on purpose. So we took the liberty to get creative here.

I had an absolute blast writing this book together with my co-author and real-life actual hero person Adam Ferner. Our original plan was to call this book Philosophical Empires, to draw attention to the outsized role that, throughout history, philosophies have often had in shaping imperialist aspirations (and still do, btw: hello, market capitalism!). But the Sales Team (who, admittedly, know infinitely more about these things than I do) thought the better of it.

You should, I hope, find The Philosophers’ Library accessible. Maybe even funny? (There’s jokes in there. Lots of philosophy jokes.) Definitely quirky.

Here is an overview of the Contents:

- Introduction

- 1 Natural divides (2500 BCE–300 BCE)

- 2 Boundary crossings (300 BCE–200 CE)

- 3 Assimilation (200 CE–600 CE)

- 4 Regimes of truth (600–1000)

- 5 Balanced states (1000-1450)

- 6 Open borders (1450–1850)

- 7 Grand narratives (1850–2000)

- Conclusion: Possible futures (2000–)

And a spread from the Introduction:

The main text of the spread reads:

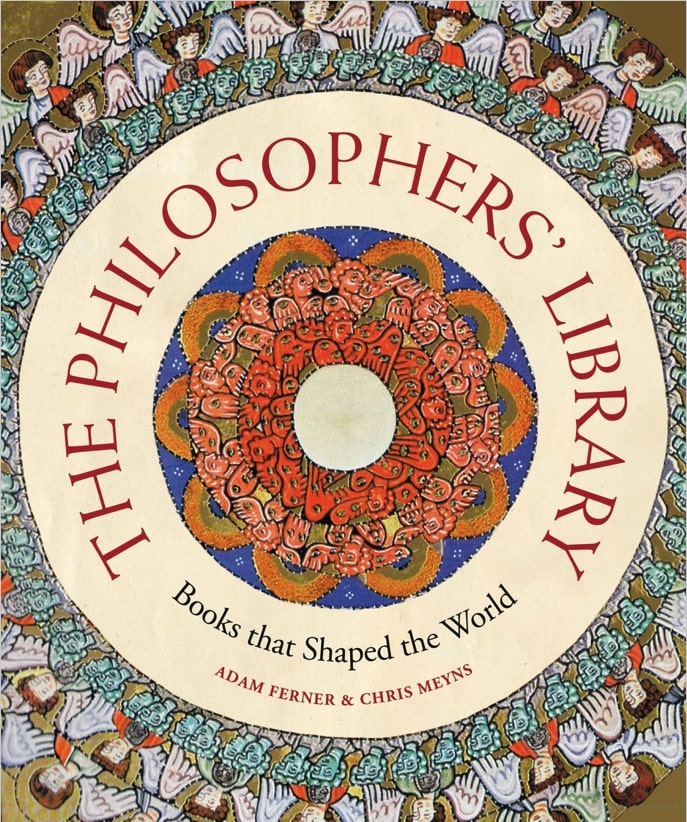

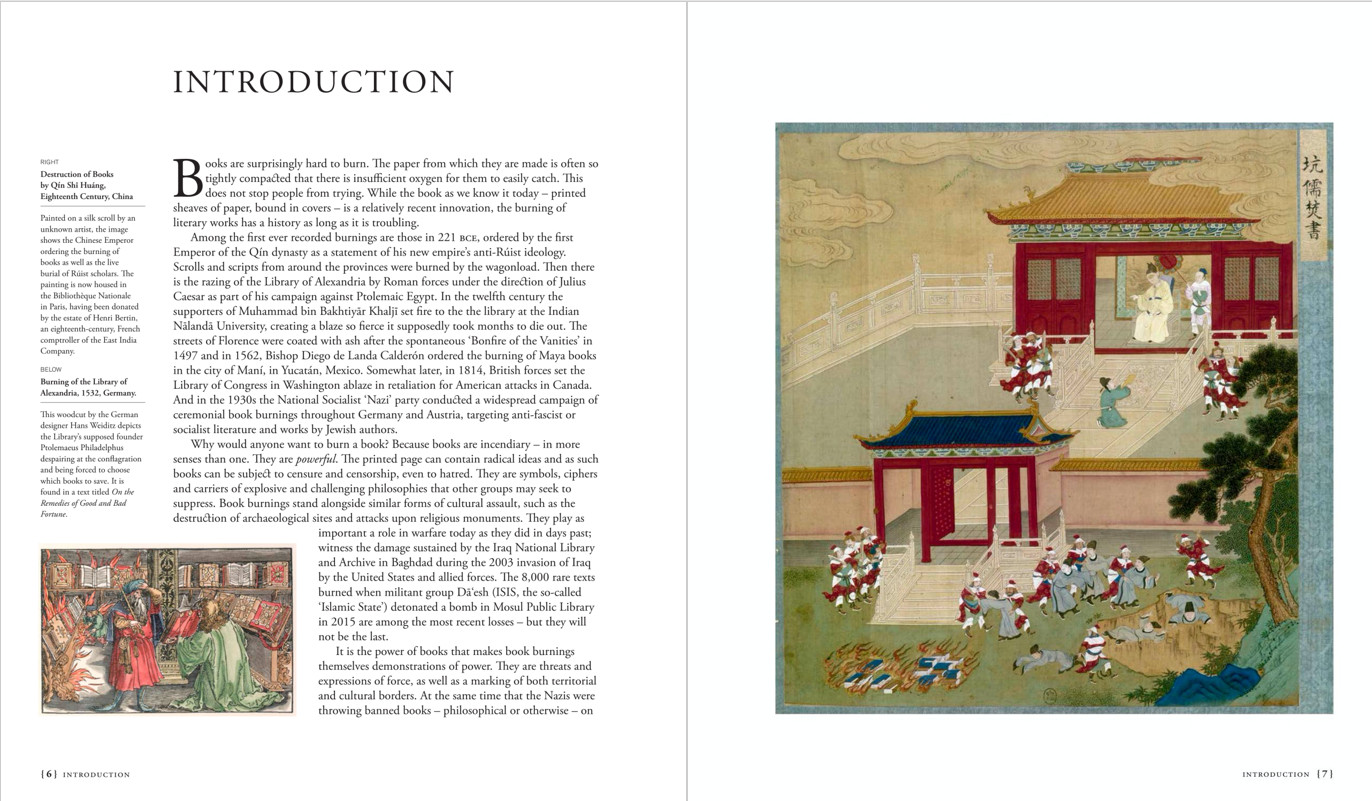

Books are surprisingly hard to burn. The paper from which they are made is often so tightly compacted that there is insufficient oxygen for them to easily catch. This does not stop people from trying. While the book as we know it today—printed sheaves of paper, bound in covers—is a relatively recent innovation, the burning of literary works has a history as long as it is troubling.

Among the first ever recorded burnings are those in 221 BCE, ordered by the first Emperor of the Qín dynasty as a statement of his new empire’s anti-Rúist [anti-Confucian] ideology. Scrolls and scripts from around the provinces were burned by the wagonload. Then there is the razing of the Library of Alexandria by Roman forces under the direction of Julius Caesar as part of his campaign against Ptolemaic Egypt. In the twelfth century the supporters of Muhammad bin Bakhtiyār Khaljī set fire to the the library at the Indian Nalanda University, creating a blaze so fierce it supposedly took months to die out. The streets of Florence were coated with ash after the spontaneous ‘Bonfire of the Vanities’ in 1497—and in 1562, Bishop Diego de Landa Calderón ordered the burning of Maya books in the city of Maní, in Yucatán, Mexico. Somewhat later, in 1814, British forces set the Library of Congress in Washington ablaze in retaliation for American attacks in Canada. And in the 1930s the National Socialist ‘Nazi’ party conducted a widespread campaign of ceremonial book burnings throughout Germany and Austria, targeting anti-fascist or socialist literature and works by Jewish authors.

Why would anyone want to burn a book? Because books are incendiary—in more senses than one. They are powerful. The printed page can contain radical ideas and as such books can be subject to censure and censorship, even to hatred. They are symbols, ciphers and carriers of explosive and challenging philosophies that other groups may seek to suppress. Book burnings stand alongside similar forms of cultural assault, such as the destruction of archaeological sites and attacks upon religious monuments. They play as important a role in warfare today as they did in days past; witness the damage sustained by the Iraq National Library and Archive in Baghdad during the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States and allied forces. The 8,000 rare texts burned when militant group Dā‘esh (ISIS, the so-called ‘Islamic State’) detonated a bomb in Mosul Public Library in 2015 are among the most recent losses – but they will not be the last.

It is the power of books that makes book burnings themselves demonstrations of power. They are threats and expressions of force, as well as a marking of both territorial and cultural borders. (…)

If you’d like to share your thoughts on anything you read in the book, feel free to drop me a note :)