Inscription Rebellion on Elizabeth Carter’s (1717-1806) Title Page

In 1758, a revolutionary text left London-based printer S. Richardson, swiftly finding its way from booksellers in The Strand and Pall Mall to the shelves of hundreds of philosophically inclined households. Supported by over 100 subscribers in an early form of crowdfunding, here was the first English translation of the complete works of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus. Contemporary sources state that the translation ‘made a great noise all over Europe’ and it long remained a standard work.

The person responsible for the translation was poet, linguist and philosopher Elizabeth Carter (1717–1806). Carter, who mastered nine languages including Greek, Portuguese and Arabic, had already made a name for herself, having published popular articles, poems, as well as translating work on Newton from the Italian. Carter was active in circles around the writer and social reformer Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800), founder of The Blue Stockings Society.

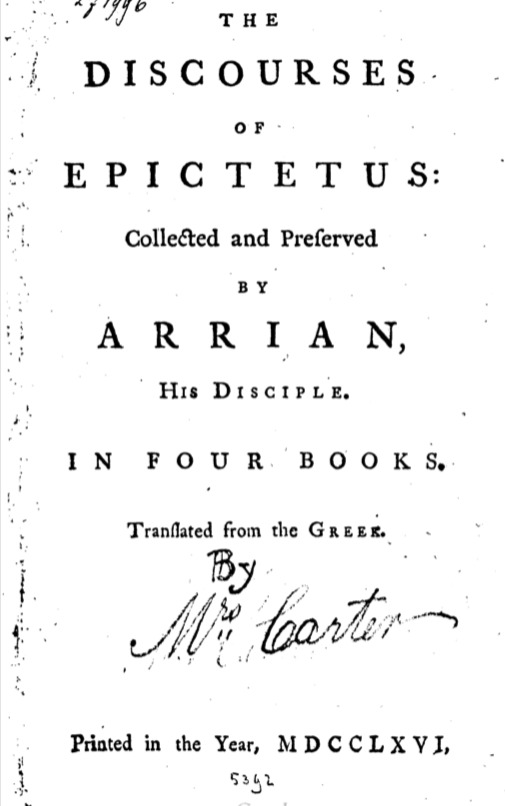

When, searching for early modern editions of Stoic texts, I came across a 1766 copy of Carter’s work, I found something curious. Its title page provided abundant information: I read the work’s title (The Discourses of Epictetus), how many books it comprises (four), print date (MDCCLXVI), and even that Epictetus’ disciple Arrian did crucial preservation work. Still, something went terribly wrong. The page forgets to tell us who did the translation. Years of painstaking work ignored. Most surprising, though, is what happened next. An anonymous individual was less than satisfied with the omission. Our anonymous friend took up a pen, dipped it in ink, and added in an elegant eighteenth-century hand:

‘… By Mrs. Carter’. Our early modern #fixeditforyou.

Why was Carter’s name omitted? Was it because she was a woman venturing into the then male-dominated field of translation? Possibly. It is also known that women are often not duly credited for their scholarship.

Or perhaps it had something to do with attitudes toward translation? Translation was often seen as derivative, inferior to creative writing. Consequently, eighteenth-century translations often remained unsigned. Carter, however, did not share this attitude. In her introduction, she emphasizes the merit of translating:

‘… and they, who consult it with any degree of attention, can scarcely fail of receiving improvement. Indeed it is hardly possible to be inattentive to so awakening a speaker as Epictetus. (…) For this reason it was judged proper, that a translation of him should be undertaken’

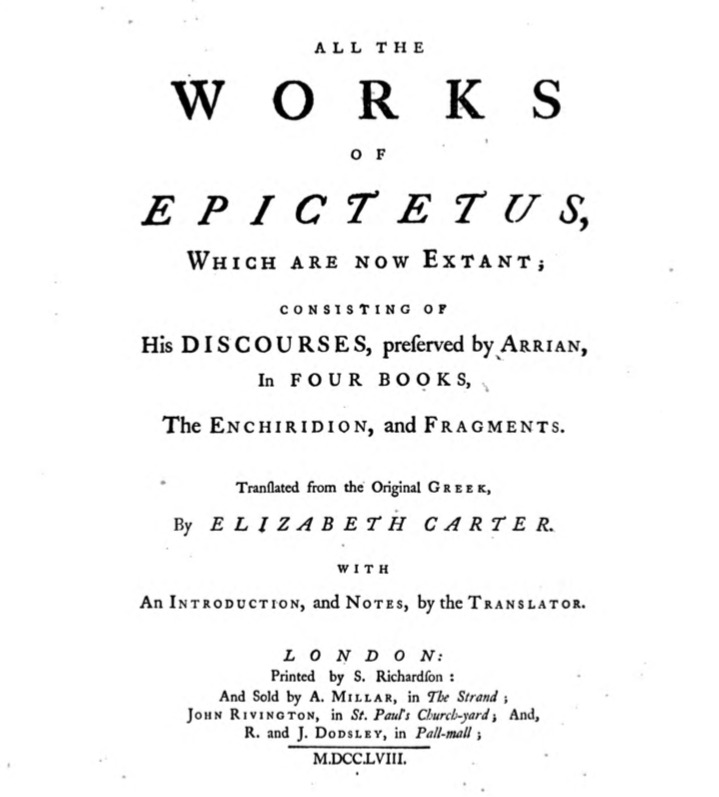

Given Carter’s stance, it should be unsurprising that the 1758 first edition of her Epictetus translation clearly marks her achievement. Whatever caused Carter’s name to disappear in the 1766 print, she had managed to get it out there on other occasions.

To be honest, why Carter’s name was omitted does not matter that much to me. What matters is what followed. Someone took up a pen and inscribed Carter back in. They did not sit back, hoping that people would somehow miraculously grasp who the translator was. Nor did our anonymous inscriber ask or wait for anyone’s permission to fix the 1766 copy’s evident wrongs. Instead, they took the initiative. Their intervention ensured that any reader of this copy would see that the translation was by Mrs. Carter.

I see a lesson in our inscriber’s action. If we want writers whose names tend to slip off pages actually to show up in the history of philosophy, it will not do simply to wait until they somehow, as if inevitably, percolate into that history. Instead, it requires active, rebellious inscribing: carving that person’s name, even if it subverts conventions.

What would an inscription rebellion look like? We can easily spot such inscriptions in scholarship—books, talks, and dissertations about people whose names disappeared from the register. Such work conforms to what the academy recognizes as legit scholarly output. But our inscriber’s proves the power of informal actions. Why not slip a list of errata into a so-called philosophy handbook that fails to mention any women or philosophers from Asian, African, South-American or Indigenous traditions? Hold a sit-in to counter yet another of those awfully dull, all-white, all-male line-ups? How about writing someone’s Wikipedia page without formal approval? Start a lending library to let people self-educate on ignored topics? Self-publish to get around the stultifying gaze (not to mention price tags) of big-name presses? How about some postcard activism?

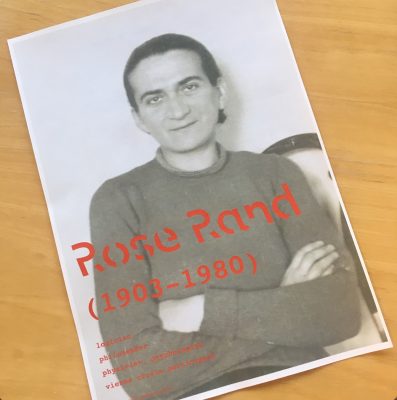

At my recent Women in the History of Philosophy lecture on the not-yet-so-well-known philosopher Rose Rand (1903-1980), I decided to ditch regular handouts. Instead, attendees got full-colour posters of Rand with some unpublished texts on the back. I yearn for these to be pinned up, adorning student bedrooms and Department corridors. Unsanctioned acts of inscribing will lead to some adorable pushback. People will tell you: ‘Chris, that’s not really philosophy!’, ‘You’re not serious’, or ‘That’s not how we do it!’. (If you’d like to add to a stream of ‘concerned’ messages currently flooding my inbox, please do.)

And you know what? These objectors are right. They are right, because indeed, inscribing the discipline’s omissions right back into it is not how it is usually done. But how it is usually done includes leaving out the women. At a certain point, perpetuating such ‘forgetting’ becomes stale. As Carter’s anonymous inscriber already saw, you fight tiresome omissions with DIY solutions.